Australia is a huge country and it still keeps its mysteries and secrets, mainly for people like me living on the other side of the world. It's very strange how electronic and experimental music and films made in Australia in the '50s and '60s didn't come to our ears and eyes as "easy" as the music and films made in other countries. From composer Percy Grainger and his inventions with Burnett Cross to the CSIRAC (one of the first digital computers used to create electronic music in the whole world), some of the most amazing experiences in sounds come from Australia. In the early days, many of the pioneers in electronic and experimental music and films had to move from Australia to Europe to reach wider audiences for their art work. Partly, it wasn't different with Arthur and Corinne Cantrill.

Arthur Cantrill (born in 1938) and Corinne Cantrill (born in 1928) are both born in Sydney. They met each other in the late '50s, when they both worked with children in Australia. Soon their love for the same subjects - especially experimental films - led them to begin a life together and to create magical and mysterious films, including the way they choose to show these films and also their soundtracks!

Arthur and Corinne are also responsible for 'Cantrills Filmnotes', from 1971 to 2000, an independent publication - dedicated to experimental films, video, installation, sound and performance arts - covering activities not only in Australia but also in New Zealand, U.S.A., Canada, Japan, The Philippines, Indonesia, France, Germany, Holland, Austria and England. All back issues are available via Arthur and Corinne Cantrill's website. In 2010, the label Shame File Music edited a compilation of the soundtracks created for their movies, from 1963 to 2009 ('Chromatic Mysteries - Soundtracks 1963 to 2009') and it is also releasing the LP 'Hootonics', containing music created by Arthur Cantrill to their 1970 feature length film 'Harry Hooton'. You can find both releases via Shame File Music website.

Arthur and Corinne are also responsible for 'Cantrills Filmnotes', from 1971 to 2000, an independent publication - dedicated to experimental films, video, installation, sound and performance arts - covering activities not only in Australia but also in New Zealand, U.S.A., Canada, Japan, The Philippines, Indonesia, France, Germany, Holland, Austria and England. All back issues are available via Arthur and Corinne Cantrill's website. In 2010, the label Shame File Music edited a compilation of the soundtracks created for their movies, from 1963 to 2009 ('Chromatic Mysteries - Soundtracks 1963 to 2009') and it is also releasing the LP 'Hootonics', containing music created by Arthur Cantrill to their 1970 feature length film 'Harry Hooton'. You can find both releases via Shame File Music website.I've contacted Arthur and Corinne Cantrill via Facebook and then via email to ask for this interview, which they kindly accepted and quickly answered. It's very nice to have this opportunity to make contact to the Cantrills, to interview them, and to know a little bit more about the early days of experimental films and music in Australia! Hope I can meet them someday! And now, the interview!

ASTRONAUTA - Arthur and Corinne, how were your lives in your childhood days and how was the very first contact that both of you had with arts, movies and music in your lives?

CORINNE - I was born in Sydney in 1928. Both parents were outside the mainstream of a narrow society - my mother a member of the Theosophical Society, my father became an active member of the Communist Party. Both were very anti-establishment, 'outsiders'. Like most families, we were badly affected by the Great Depression, but my parents were resourceful, and we managed. Their marriage was unhappy, and it had a negative affect on me - it left me detached from both parents, and feeling very alone. I had few friends.

I did very well at school, and won a bursary to a prestigious secondary school, when I was 12. The biggest influences on me were the outstanding teachers at school.

During the 1930s I was deeply aware and frightened of the events in Nazi Germany, Spain, Italy and the Japanese invasion of China, especially because I was Jewish.

From quite a young age, I went alone to the movies on Saturday afternoons - 99% of the features were from Hollywood, plus newsreels, March of Time, Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars, Our Gang, Laurel and Hardy, Chaplin, Robert Benchley, etc. The variety of 'supports' was more interesting than most features.

The other cultural influence, from a young age, was reading. I had a lot of good books, and even devised my own catalogue system for them.

My mother was a good amateur pianist, and I grew up listening to her playing classics. The other big cultural influence was radio, especially the national non-commercial station of the Australian Broadcasting Commission. It had good music programmes, radio theatre, and especially a great children's programme each day: The Argonauts' Club. They encouraged children to be interested in art, music, nature study, poetry, and we listened to the great classics of 'The Odyssey', 'The Iliad', Viking legends, etc. etc. We were encouraged to send in our art work, poems, etc.

By the age of fourteen I was no longer interested in Hollywood movies; instead I experienced live theatre. There was in Sydney, a remarkable group - The Independent Theatre - which presented the classics of the repertory theatre: Shakespeare, Molière, Chekhov, Ibsen, Strindberg, G. B. Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Eugene O'Neill, the Greek tragedies, as well as theatre for children. I went to every production. After the war, in 1945, films from France, Italy and England arrived and were shown in the one Syndey 'art house' cinema. They were so different from the Hollywood films I'd seen as a child, and they were inspiring... (But nothing from the Soviet Union until the 1950s.)

In 1943, I left school when I was 15. This caused great unhappiness to my teachers at high school, who believed I was ruining my life. Because the War was raging in the Pacific, many opportunities were there to temporarily engage in interesting work - until the men returned from the War. I was given a rudimentary training in laboratory procedures, and then work at the Forestry Commission to keep their small mycology laboratory functioning.

In 1943, I left school when I was 15. This caused great unhappiness to my teachers at high school, who believed I was ruining my life. Because the War was raging in the Pacific, many opportunities were there to temporarily engage in interesting work - until the men returned from the War. I was given a rudimentary training in laboratory procedures, and then work at the Forestry Commission to keep their small mycology laboratory functioning.I developed a strong interest in Botany, and decided to study the full range of Botany subjects at Sydney University, as an unmatriculated student (meaning I could do the courses, and the exams, but get no qualifications for studies.)

I was an exceptional student, and was allowed to work as one of the Demonstrators for the First Year Botany practical classes (supervising the practical work, answering questions, making corrections.) This opportunity was also because more experienced men were fighting in the War.

Parallel with this involvement with Botany/Science, I moved in a circle of friends who were a few years older than me, people who were writers, artists, musicians, poets. We discussed literature, went to art exhibitions, and tried to find out as much as possible about contemporary art in Europe. Australia was very culturally isolated, and we were frustrated by this.

In February, 1948 - I was 19 - I left Australia for five years to experience the rich culture of Europe. I was no longer interested in Botany/Science; instead I wanted to immerse myself in the arts, especially in music.

I lived in London for a year, attending evening classes at Morley College, going to the theatre, concerts, cinemas, the galleries and museums.

In 1949, I left London to live in Paris for 18 months - a much more beautiful city, a richer cultural life. I wrote for the Australian magazines about living in Paris, as a source of income.

I also became a member of the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin - it ran several programmes a week - very wide-ranging: cinema classics, political films, new work. There were also dozens of small cinemas in Paris showing the whole gamut of cinema.

Late in 1950, unable to get my student visa renewed, I left Paris to live in Rome for the next two years. It was refreshing to be in Italy after the social coldness towards foreigners in France! Italian society brought out one's human/humane qualities.

Italians were articulate, and open in analyzing and discussing their lives, especially their experiences during the Fascist period and the war, and the German occupation.

Rome was also a great centre for Cinema, for music and for Opera.

I supported myself by giving English lessons to a wide range of people, including children. Italians still believed that an educated person must speak four languages. The families and people to whom I gave English lessons became friends - almost family. I traveled widely in Italy. During the 1951 summer break I went to Yugoslavia as part of an International Youth Brigade to work on the Dobuj - Banja Luka Railway for 3 weeks. After that I went to Austria and Germany for four weeks - the situation in Germany was bleak, even six years after the war.

In 1952, a close friend from Sydney joined me in Rome, and we traveled to Spain, Portugal, France, Holland and then to Scandinavia. I decided to stay in Copenhagen, again teaching English, until I left Europe in March, 1953 to return to Sydney.

The social climate in Denmark was very interesting. The sense of social justice for all people was very strong - very different to the class system in Italy and other parts of Europe.

I don't remember going to the cinema (or theatre) once in Copenhagen! I went to concerts, and socialized, and read a lot (thanks to The British Council Library.)

At this time Europe seemed to be moving towards another war - Stalin seemed mad and unstable. I had more problems about work permits/visas, and in spite of good friendships, it seemed I would always be an outsider.

I borrowed the fare home from my father, and returned to Sydney in mid-1953.

The experiences of the great cities, the landscapes, the art and especially the architecture of Europe had been a privilege. But parallel to that had been the despair about the effect of war(s) on countries and societies, and the minds of individuals. I am mindful of this, right to this day.

In Sydney, I first had work as a salesperson on commission, where I earned incredible money. It exhausted me, so I had to stop. By chance, I met a remarkable woman who had pioneered children's self-expression through art. She had several Children's Creative Leisure Centers in Sydney where a range of activities were encouraged (but not 'taught') - where the people who worked there provided the materials for the children, and encouragement. I worked there, and found this work much more interesting.

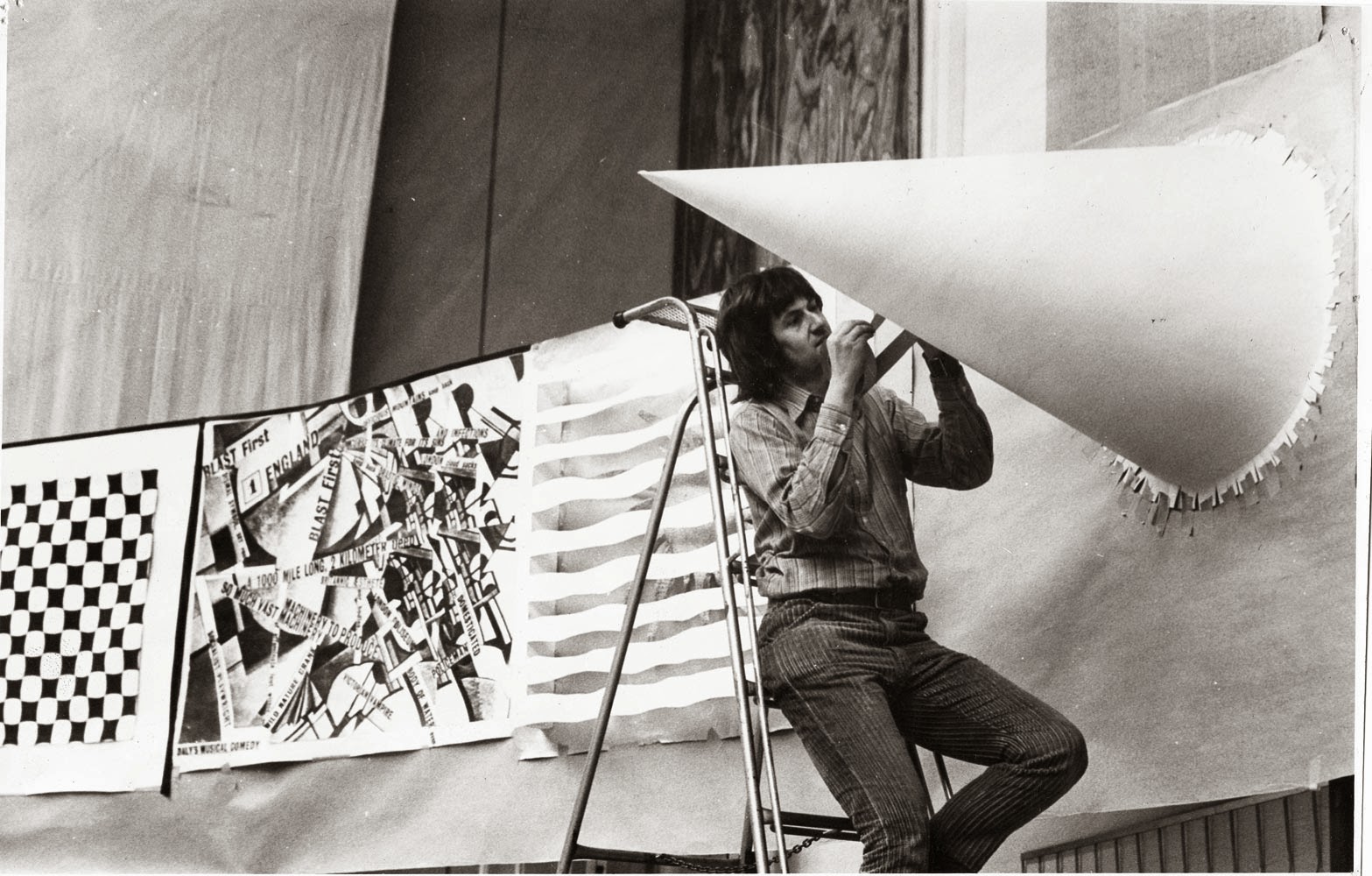

.jpg) ARTHUR - Childhood days!

ARTHUR - Childhood days!I tended to be a loner, with a few friends. I was not interested in sport. My family was not at all cultured - there were few books in the house - but they sent me to piano lessons (I still like to play the piano) and I had rudimentary violin lessons in first year at high school in order to swell the school orchestra, using the violin my father used as a boy. There was no music after first year. Primary school art education had been very uninspiring, and there was no art at all at high school. I was not taken to art exhibitions by my parents - the only museum I attended was the natural history museum.

My first seven years were dominated by Second World War - there was a real threat from the Japanese after they bombed Darwin, and were sending small submarines into Sydney Harbour. My father volunteered to do harbour patrol in his motor yacht. We occasionally had air raid scares.

Guided by a high school friend, I became interested in classical music and listened to the music programs on the radio as well as the children's program, 'The Argonauts' Club', that Corinne mentioned - the story of Jason and The Argonauts and the search for the Golden Fleece. I started collecting 78 and LP records.

My life suddenly changed when I was at age 12 I discovered a children's puppet theatre, conducted by the organization mentioned by Corinne that had pioneered children's creative leisure centers. I threw myself into making puppets (glove and marionettes, or string puppets), painting scenery, writing plays, rehearsals and Saturday afternoon performances. We participated in a public performance at The Independent Theatre, and I directed the puppet theatre for a year when the regular director went on tour.

My first involvement in film production was when I appeared in two educational films on puppetry that were made at the puppet theatre. (Later, some of our first films in the early 1960s were films for children, used on television in Australia, New Zealand and Ireland.)

I left the puppet theatre at age 19 when I became employed full-time by the organization at another children's centre in Sydney. Working there widened my circle of friends who were involved in the cultural life of Sydney, and through them I met the anarchist poet-philosopher Harry Hooton, who influenced my practice in art. Later in 1970 Corinne and I made a feature-length film, 'Harry Hooton', inspired by his philosophy.

From the age of seven or eight I had regularly gone to the Saturday afternoon children's cinema programs of animated cartoons, adventure films, serials. I had a choice of three suburban cinemas - two within easy walking distance, The Ritz and The Odeon, and the third a short tram ride away, The Boomerang. I began to be seriously attracted to cinema in my teen years - some European 'art house' films were being shown in Australia in the 1950s and there was a cinema devoted to these films in the city, The Savoy. Clouzot's 'The Wages of Fear' impressed, and I remember seeing Fellini's 'La Strada' and feeling inspired that film could be art.

The film festivals showed some experimental films in the 1960s, and cinema groups showed what was available - Soviet films, and films from various foreign embassies.

I was impressed by the sound compositions coming from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which were occasionally broadcast on the radio by Australian Broadcasting Commission. (Later when I was working as a film editor at the BBC I asked the Radiophonic department to compose a short piece for a documentary I was editing.) I became aware of the possibilities of experimental music.

ASTRONAUTA - How and when did you meet each other?

CORINNE - I met Arthur Cantrill through the children's creative leisure centres - he also worked in one of the Sydney Centres.

CORINNE - I met Arthur Cantrill through the children's creative leisure centres - he also worked in one of the Sydney Centres.At the end of 1955 I left Sydney to live in Brisbane. I opened a centre for children there, and ran it, without any financial support, on Saturdays and school holidays with two friends, for children who lived in very disadvantaged families.

Arthur came up to Brisbane to help me with a school holiday workshop in 1959.

That is how we came into filmmaking: our parent organization in Sydney was already making 10 minutes documentaries about the activities at the Centres for national TV - Arthur had participated in several of these short films.

Because the work we were doing with children in Brisbane was different, we suggested that we would like to make a series of films for the parent organization. They agreed, and paid us a fee for each film.

With that money we bought our first film equipment. At that time the National TV broadcaster, ABC TV, was actively supporting filmmakers. We made a number of films for children's programmes, including a ten-episode shadow puppet production of Homer's 'The Odyssey'. We also made a large number of short films (4 to 5 minutes long) as fillers between programmes, as the ABC carried no advertising. With these short films we experimented with different ideas, in image, and in sound.

We had an important collaboration with the composer, Larry Sitsky, who was also living in Brisbane at this time - a gifted and intelligent man. He did the sound-tracks for six of our films.

There was also a good film Society - The Brisbane Cinema Group - run by Stathe Black, who located all possible experimental films available in Australia then, through the German, French, Canadian embassies, and through other film libraries, and programmed these for the monthly screenings. (We had the first overview screening of our work through the Brisbane Cinema Group in 1965, as a farewell event before we left Australia in August 1965, to go to London.)

ARTHUR - As Corinne said, in the late 1950s we were both employed by the organization that conducted free 'Creative Leisure Centres', based on Herbert Read's "education through art" philosophy, where children could explore all aspects of art and craft with a minimum of instruction.

In 1959 I was sent to assist Corinne set up a demonstration of child art activities in Brisbane, outside a public library, and we stayed together, quickly deciding to begin a filmmaking career. Our first films were a series showing children exploring art and crafts and puppetry, which were used on television.

ASTRONAUTA - How was the experimental movie scene in Australia in the '60s? What are the best memories that you have from your early days in experimental movies (and the respective soundtracks)?

ASTRONAUTA - How was the experimental movie scene in Australia in the '60s? What are the best memories that you have from your early days in experimental movies (and the respective soundtracks)?CORINNE - There were quite a number of other people in Australia (in Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney) also exploring the possibilities of film, and of sound - some of these people we were in touch with, and some of them we knew and had seen their work.

ARTHUR - Some interesting experimental filmmaking was done in Adelaide in the 1940s and 1950s, mainly by East European artists who emigrated to Australia. (We covered this in an issue of our film magazine, 'Cantrills Filmnotes'.) And in Sydney, filmmakers such as David Perry, Aggy Read and Albie Thoms were making experimental films from the 1960s, influenced by the American experimental film movement.

Our first experimental films were made around 1963, when we were living in Brisbane, and I made my first sound compositions for these films. We also commissioned film music from innovative composers, but the results were generally not so satisfactory as when I composed for the films. My results were less 'musical', more abstract and more closely related to the images.

ASTRONAUTA - What were the main differences that you found when you moved to London in the late '60s?

CORINNE - London in the 1960s was a great meeting place for artists from across the world - in all media. It was a very stimulating place to be - the Arts Laboratory ran many events in experimental theatre, music, film, every night of the week - it had a series of small spaces so that there could be two or three different performances taking place each night.

Bob Cobbing's bookshop, 'Better Books' was also a place where interesting film events took place.

In 1967/68 (Dec./Jan.) we attended the Knokke Experimental Film Competition in Belgium, organized by the great, late Jacques Ledoux. People came from across the world to be there - there was a Gregory Markopoulos Retrospective, the premiere of Michael Snow's 'Wavelength', with separate sound on a powerful sound - generating device, lots of films from USA - Robert Nelson, Gunvor Nelson, Will Hindle, Paul Sharits; really powerful films from Germany and Austria, from Japan, and from England - Stephen Dwoskin, Malcolm Le Grice, Don Levy, Yoko Ono (whose events and performances we knew already from London) - so it was very full on, and a turning point in our filmmaking lives.

We had been wavering about making films, or animated films, but after Knokke we knew we wanted to work in this more experimental area.

Just before we went to Knokke, we had also been to a three-day Cambridge Animation Festival - the main retrospective there had been for Alexandre Alexeieff, (he was there). We also saw Red Grooms' 'Fat Feet', a lot on interesting animation from France, and from Japan, especially by Yoji Kuri.

The following year, late in 1968, the Cambridge Animation Festival featured the work of Len Lye - he was there - that was a very exciting event and he was such a dynamic person to encounter. And important, too, because he came from New Zealand, a tiny little outpost - much smaller than Australia.

During 1968, after Knokke, we made several important films: 'Red Stone Dancer' - a tribute to the life-changing event of Knokke, and then 'Moving Statics', an important collaboration with abstract theatre/mime artist, Will Spoor, from Amsterdam, but performing in London at the Arts Laboratory. Will Spoor was great to work with, as he understood the possibilities of film, and live animation techniques. He also created unusual sound-effects with his voice, with objects, etc, so between the three of us, it was a fantastic collaboration - very intense and intelligent. (Will Spoor is still alive - he is 86 - we had a recent visit from one of his young friends.)

We made two other films with Will Spoor: 'Rehearsal at the Arts Laboratory', and 'Imprints' (the latter film made from fragments of trims from 'Moving Statics'.)

In March, 1969, we returned to Australia where Arthur had been awarded a Fellowship in the Creative Arts at the Australian National University in Canberra.

In March, 1969, we returned to Australia where Arthur had been awarded a Fellowship in the Creative Arts at the Australian National University in Canberra.That was a period of intense work, where we made several important films, and also did our first Expanded Cinema performances and multi-screen, and multi-image works, - and films such as projecting onto a burning screen (in the open air), onto water, films projected onto objects, textured screens, moving screens, 3-dimensional screens. All these films required Arthur to work on the sound as well as the image.

I should say that we both had a strong interest in all manner of music and sound: classical, ancient, ethnic, avant-garde, folk, etc. We were also working with sounds from the natural world: birds, insects, water, wind, storms, the ocean, waterfalls - sound as music.

We've always worked on our films (editing, sound, etc.) at home, because of our children when they were younger, and generally speaking, we haven't worked with other professionals in the film or sound areas. There have been notable exceptions: our involvement with Larry Sitsky, the composer Chris Knowles, the poet Garrie Hutchinson, the sound poet Jas H. Duke; and in recent years with musicians improvising live to our films in special performances: Robin Fox, Clinton Green and others.

All our work has been done at very low cost, doing everything ourselves.

We no longer make new films, because we are burdened with the responsibility of a vast body of work from more than 50 years. We are not interested in working in digital. We've both got health problems (we are not young) and we need to spend a lot of time getting our existing work in order - not just the films and the sound - but a vast library of books, magazines, papers, photographs/stills/slides, posters, documentation, etc.

We have shown our work all over the world (regrettably we haven't been to South America, though one of our films was shown at a festival in Buenos Aires some years ago.) Travelling now is almost out of question.

ARTHUR - We worked in London for four years in the late 1960s, making both art documentaries and experimental films, while I worked as a film editor at Halas and Batchelor Cartoon Films and the BBC. As Corinne said, we became more aware of the experimental film movement in U.S.A. and Europe, especially when we attended the Knokke-le-Zoute experimental film festival in Belgium. There, in the innovative use of film sound (as in Michael Snow's 'Wavelength') confirmed our approach to sound. And we encountered important artists there. We had a long conversation with Yoko Ono, for example. The Knokke experience made us decide to move to full-time experimental filmmaking.

ARTHUR - We worked in London for four years in the late 1960s, making both art documentaries and experimental films, while I worked as a film editor at Halas and Batchelor Cartoon Films and the BBC. As Corinne said, we became more aware of the experimental film movement in U.S.A. and Europe, especially when we attended the Knokke-le-Zoute experimental film festival in Belgium. There, in the innovative use of film sound (as in Michael Snow's 'Wavelength') confirmed our approach to sound. And we encountered important artists there. We had a long conversation with Yoko Ono, for example. The Knokke experience made us decide to move to full-time experimental filmmaking.ASTRONAUTA - You also created the soundtracks and sound effects for your movies. What were the techniques that you used to do that?

ARTHUR - For the first experimental soundtracks in 1962-63 I used a Nagra reel-to-reel tape recorder together with our Ferrograph tape machine to produce tracks largely of piano effects - strumming strings and keyboards sounds, speeded up, slowed down and reversed, and using the Nagra's separately controlled line and mike inputs to mix sounds. (One of these tracks, for the film 'Galaxy', 1963, was released in the CD 'Chromatic Mysteries, soundtracks 1963-2009', published by Shame File Music in 2010.) For other early soundtracks I mixed, edited, and electronically altered sound recorded on our Nagra (field recordings of birds, water, piano and percussion effects, for example), using techniques akin to musique concrète. The aim usually was to find an audio equivalent to the imagery, though sometimes there was a disjunction between sound and image.

ARTHUR - For the first experimental soundtracks in 1962-63 I used a Nagra reel-to-reel tape recorder together with our Ferrograph tape machine to produce tracks largely of piano effects - strumming strings and keyboards sounds, speeded up, slowed down and reversed, and using the Nagra's separately controlled line and mike inputs to mix sounds. (One of these tracks, for the film 'Galaxy', 1963, was released in the CD 'Chromatic Mysteries, soundtracks 1963-2009', published by Shame File Music in 2010.) For other early soundtracks I mixed, edited, and electronically altered sound recorded on our Nagra (field recordings of birds, water, piano and percussion effects, for example), using techniques akin to musique concrète. The aim usually was to find an audio equivalent to the imagery, though sometimes there was a disjunction between sound and image.ASTRONAUTA - Shame File Music is releasing "Hootonics", an LP containing music that you created for a film of yours in 1970. How was the music created for this soundtrack?

ARTHUR - For the 'Harry Hooton' film I continued using the techniques described above. To our Nagra and Ferrograph tape records we added the semi-professional Revox. This machine could feed the signal at the playback head back into the recording head which was useful for generating reverberation and white noise effects that could be controlled with some precision. I recorded the sound output from mainframe computers in experimental use in 1969 and electronically altered and mixed it. Also 'found sound' (birdcalls, radio news broadcasts, for example) was collaged together and mixed. The sound for 'Harry Hooton' was transferred to 16mm magnetic film which I further edited before it was mixed in a professional dubbing theatre.

ARTHUR - For the 'Harry Hooton' film I continued using the techniques described above. To our Nagra and Ferrograph tape records we added the semi-professional Revox. This machine could feed the signal at the playback head back into the recording head which was useful for generating reverberation and white noise effects that could be controlled with some precision. I recorded the sound output from mainframe computers in experimental use in 1969 and electronically altered and mixed it. Also 'found sound' (birdcalls, radio news broadcasts, for example) was collaged together and mixed. The sound for 'Harry Hooton' was transferred to 16mm magnetic film which I further edited before it was mixed in a professional dubbing theatre.Later we acquired a second Revox machine and a graphic equalizer which added to the sound mixing capability. The 'bonus' composition currently offered with 'Hootonics' LP is a recent composition, 'Cicada Mix', (not a film soundtrack). It uses cicadas, piano, violin and xylophone effects, altered with the Revox reverb/white noise facility.

ASTRONAUTA - Some of your films are being shown at CCCB/Barcelona, during Xcèntric 2014. So it seems that 2014 is beginning as a very busy year for you. What are your plans for the future, new films, new albums, next travels?

ARTHUR - And one of our films showed at Culturgest in Lisbon at the same time as Barcelona. Doubtless there will be other screenings around the world, but we often aren't aware of them until later, as they borrow films from various collections. Recently we've been adding sound tracks to some of our previously silent movies, such as 'Imprints' and 'Meteor Crater at Gosse Bluff'.

Our next project is a multi-screen retrospective, looking on our film career, speaking to film extracts and complete films, for the 2015 Castlemaine State Festival. At the moment we have no plans to travel overseas.

CORINNE - I doubt that 2014 will be a busy year for us professionally! No plans for new films! New audio albums we leave to Shame File and Clinton Green! No travels either. We had a major retrospective, 'Grain of the Voice' in Melbourne at The Australian Centre for the Moving Image in 2010 and a very good exhibition in 2011, also at ACMI - 'Light Years' - posters, stills, artefacts, the magazine, and films and extracts running on four monitors in the Gallery there.

In 2015 we are expecting to have another Retrospective in Castlemaine (where we now live) in their Festival of the Arts - we're trying to see if technically it can be done here.

For the rest, we leave it to others to borrow our work from collections which hold copies of our films and programme them. Our work is held in various collections in Australia, and in Berlin, Paris, and in non-lending collections in North America (MoMA, CalArts, Harvard, etc.) and in non-lending collections and Archives in Europe.

We can't be bothered with the work involved in making good quality digital transfers of our films - as well as it being very expensive. ACMI digitalized a few films for the 'Light Years' Exhibition, and University of Technology in Syndey recently digitalized a major film for us - but that's it. Living out in the country now makes that even more problematic. This is probably the acceptance of the impermanence of material things.

A final comment! Are you aware of the remarkable magazine, 'Cantrills Filmnotes', which we published for 30 years from 1971 - 2000? (Issues #1 - #93/100.) It has been a major contribution to the international experimental film scene: concentrating on personal, avant-garde, experimental work in film, video, sound, animation, ethnographic, performance, multi-media, and multi-screen. And focusing on work from the Pan-Pacific region, as well as from Europe - just covering the people who interested us - well-known people like Nam June Paik, Gregory Markopoulous, George Kuchar, to unknown and lesser known people.

There is not a single set of Issues of 'Cantrills Filmnotes' in South America, while we still have about 15,000 back issues at home! Think about that, perhaps you could be the first person in South America to have a set of issues, or even just some of them!

ARTHUR - In more recent years we've mixed and edited sound on the computer, rather than using analogue methods -- although I do miss mixing sound in real time -- it had a sense of performance about it! As well, recent film soundtracks are played from a CD, rather than having an optical track on the film print. This means much better quality of stereo sound, which is effective in films such as 'Meteor Crater at Gosse Bluff', a two- or three-screen landscape film, as the stereo adds a spatial effect. (This track is on the Shame File CD 'Chromatic Mysteries: soundtracks 1963-2009'.)

More infos: www.arthurandcorinnecantrill.com